Teaching looks so easy: all we have to do is stand up and talk. Lots of us can do that! So, if this is all there is, could an AI chat box one day become an effective classroom teacher?

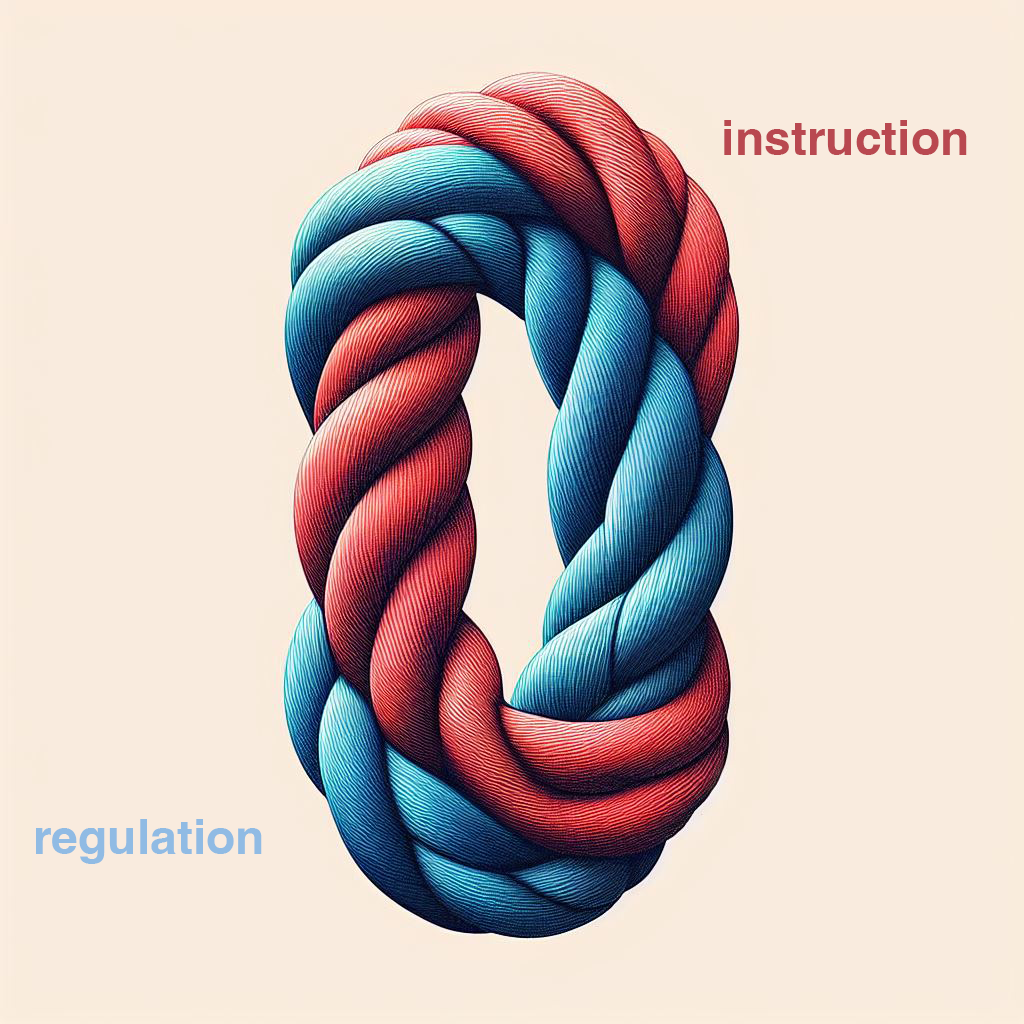

Obviously, a fundamental part of teaching is about instruction. Instruction is the transmission of knowledge and skills from an expert to a novice student.

Teachers learn to select the appropriate knowledge and skills, learn to use appropriate language, lesson sequencing and techniques of communication.

These allow ideas to be received and understood by their students.

AI can help teachers prepare for each of these areas, although how teachers control these processes is crucial to their chances of using AI successfully, as we shall see in future posts.

However, content is not the only thing that is taught in lessons.

A second discourse runs in parallel alongside the instruction.

This regulates students’ behaviour and develops their social attitudes.

Instruction and regulation are so completely intertwined with each other, that they are inseparable.

This post looks more carefully at how teachers regulate students’ behaviour and its implications for how AI can be instructed to plan lessons.

The regulation of students’ behaviour in schools in England is increasingly controlled by the Academy or even the Academy Trust. Individual teachers have much less control over this than they did a generation ago. Similar trends can be seen across the world.

The regulation is a series of rules that shape how students should behave in school:

- how they should dress,

- behave in corridors and classrooms,

- how they should walk between rooms

- how they should talk to teachers and to each other.

These behaviours create compliance in students. Students who cannot or will not comply can expect a series of sanctions of increasing severity. These behaviours can be taught to AI easily enough, since they are usually enshrined in published school policies. AI would be discouraged from saying things that were against the school rules.

It would also be relatively easy to train AI to adopt certain pedagogical styles used by teachers, such as scaffolding, retrieval practice, modelling, recall and interleaving, by including a description of the practices as part of the initial prompts. Later prompts such as “be a classroom teacher that uses the technique of retrieval practice to produce…”, could be used to create useful classroom materials.

Giving students unrestricted access to AI could cause problems, if the topic being studied involves ethical or moral discussions.

All teachers are expected to abide by the “ethos” of the school, which includes upholding shared values. These include agreed attitudes to relationships education, citizenship, and social attitudes. These are included as part of the regulation discourse and should be embedded in all lessons.

Unless AI is specifically trained to produce answers consistent with a school’s ideology, then it might be able to produce answers that would make class teachers and students feel uncomfortable or embarrassed. See my earlier post on ‘Can AI become a school tutor?’ for more on this.

AI has a huge potential to become a reliable assistant for teachers, but first it needs to be taught what a teacher’s job actually involves, which is far more than standing up and talking.

This the first of a multi-part series that uses the ideas of the pedagogic device developed by Basil Bernstein to explore the potential impacts of AI on teaching in schools. It draws on work undertaken by Neil Ingram on Pegagogy 3.0 for the Hewlett Packard Catalyst initiative.