The Oxford Biology primer contains a number of case studies on the evolution of familiar and unusual organisms, from finches to giraffes, peppered moths to wood rats!

Here are some pages that give a feel for the book.

Darwin’s finches have captured people’s imaginations ever since he first described them. In the 1970s they hooked Peter and Rosemary Grant, evolutionary biologists who were interested in the forces that drive evolution. They thought Daphne Major, one of the smallest islands of the Galapagos, would be a perfect place to study selective forces because it is uninhabited, and so small they would be able to become familiar with every single bird on the island. Like Darwin, they went for two years: their research there lasted 40!

They began their studies on Daphne Major in 1973. Every bird was captured, a numbered ring placed on its leg, and they recorded other features such as beak size. The birds were called medium ground finches, Geospiza fortis. Their diet was mainly seeds, and they showed considerable variation of beak sizes, from relatively small to relatively large.

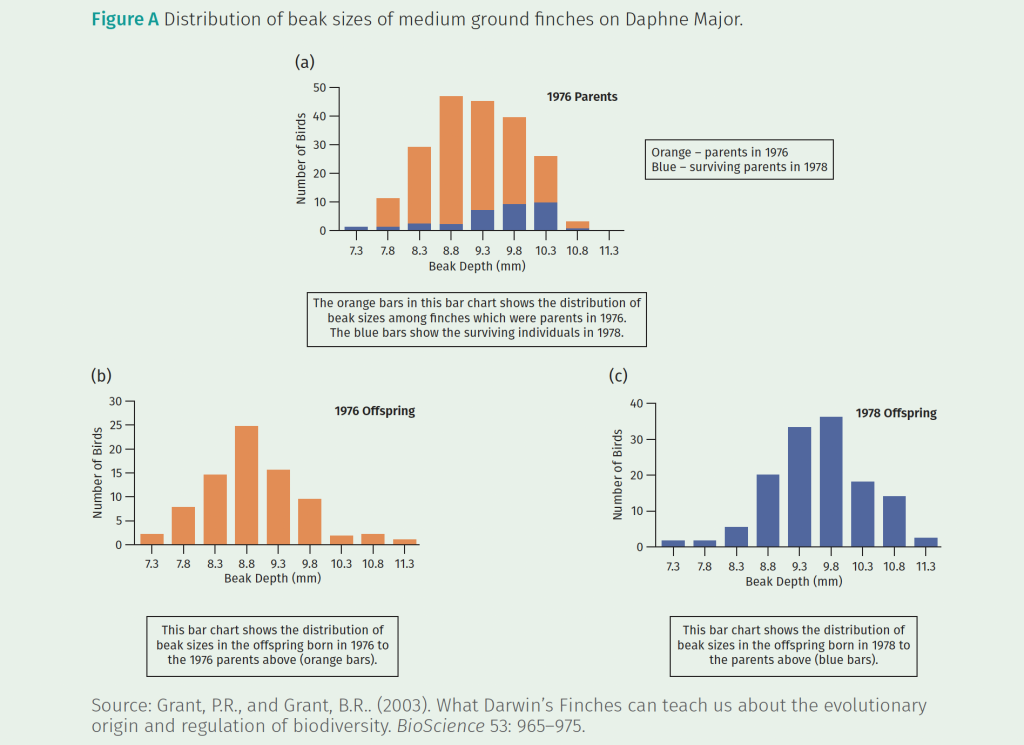

In 1977, there was a prolonged drought and many of the plants on the island died. Those that were left had very large, hard seeds. Heartbroken, the Grants could only watch as natural selection took place before their eyes and dozens of birds died of starvation. By the end of the drought they were amazed to see that the distribution of beak sizes in those medium ground finch adults which had bred the previous season had changed completely.

Look at Figure A. Can you see what happened during the drought? Only the birds with the bigger beak sizes survived. Furthermore, the distribution of beak sizes in the offspring was completely different to what it had been before the drought: the modal group had moved from 8.8mm to 9.8mm! Why do you think this happened?

In 2003, a drought similar in severity to the 1977 drought occurred on the island. However, late in 1982 a breeding population of large ground finches (Geospiza magnirostris) had become established on the island. This species has a diet overlap with the medium ground finch (G. fortis) and were competing for the larger seeds. Following the drought, the medium ground finch population had a decline in average beak size, in contrast to the increase in size found following the 1977 drought (see Figure B).

The Grants hypothesized that the smaller-beaked individuals of the medium ground finch may have been able to survive better this time by being able to eat smaller seeds, avoiding competition for large seeds with the larger ground finches G. magnirostris. The 2003 drought and resulting decrease in seed supply may have increased competition between G. fortis and G. magnirostris, particularly for the larger seeds which had enabled survival of the medium ground finches 25 years earlier. As they had larger beaks, the population of G. magnirostris had a competitive advantage when it came to eating the larger seeds. This led to the decrease in average beak size among G. fortis despite the drought conditions being very similar.

Darwin had hypothesized that the changes leading to speciation happen very slowly. Looking at the wildlife around us we get the impression that species stay the same from year to year, and this is probably why most people in the time of Darwin, including Darwin himself until after he’d returned from the Galapagos, did not believe in the transmutation (changing from one kind to another) of species. However, the Grants have demonstrated that perhaps we are simply not observant enough. Close observation of a species in the wild can show significant fluctuation in appearance, caused by the selection pressure of a mix of biotic and abiotic factors, over a relatively short period of time.

As Jonathan Losos, a Harvard evolutionary biologist, has observed, ‘Perhaps the biggest contribution of the Grants’ work is simply the realization not only that evolution can be studied in real-time, but that evolution doesn’t read the textbooks.’

The average PhD research project lasts only three years. What are the implications of this for studying long-term processes such as ecological change and evolution?